Sentiment Speaks: Why Do We Rely On News?

Sentiment Speaks: Why Do We Rely On News?

Well, that was quite the eventful week. We had a Fed announcement, and all the market geniuses were quick to attribute the cause of the 3% decline to the Fed announcement. However, this is nothing more than a foolish and very superficial perspective, which evidences their lack of true understanding of how our markets work.

As I have said often, while news can act as a catalyst for a market move, the substance of the news is really irrelevant in determining the direction of the move. In fact, we have seen many moves through market history which have not even been supported by the news. In fact, in1988 there was a study conducted by Cutler, Poterba, and Summers entitled “What Moves Stock Prices,” which supports my perspective.

Within their study, they reviewed stock market price action after major economic or other type of news (including major political events) in order to develop a model through which one would be able to predict market moves RETROSPECTIVELY. Yes, you heard me right. They were not even at the stage yet of developing a prospective prediction model.

However, the study concluded that “[m]acroeconomic news . . . explains only about one fifth of the movements in stock market prices.” In fact, they even noted that “many of the largest market movements in recent years have occurred on days when there were no major news events.” They also concluded that “[t]here is surprisingly small effect [from] big news [of] political developments . . . and international events.” They also suggested that:

“The relatively small market responses to such news, along with evidence that large market moves often occur on days without any identifiable major news releases casts doubt on the view that stock price movements are fully explicable by news. . . “

Interestingly, even after everyone was initially quick to jump on the bandwagon that the Fed was the cause of the decline, the following days saw some analysts and writers begin to question what was really said by the Fed that supposedly caused such a reaction. And, it seems the consensus now is that there really was no surprise to what the Fed said, which has them questioning the reason for the decline.

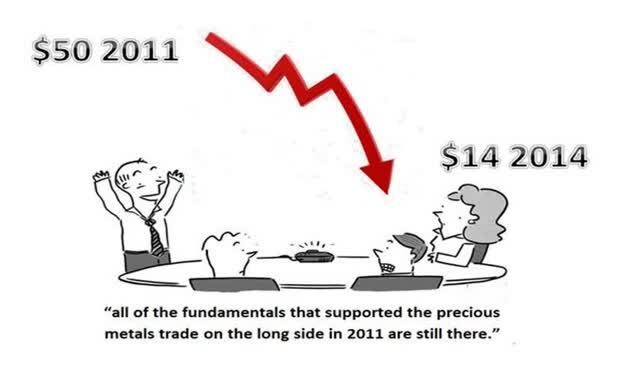

While I was watching a financial news show, one of the commentators noted that the "[f]undamentals of the market are remarkably solid." So, he did not really understand why the market tanked as it did. And, then I remembered where I heard something similar from 2011-2014:

Yesterday, I read one article wherein the author outlined a similar perspective:

“There is absolutely nothing new in either of these issues, but for some reason, in a soundbyte, short-attention-span world, the market acts like it is seeing something new.”

Another author noted something similar:

“Markets reacted violently to yesterday's FOMC meeting despite the meeting containing few surprises. . . The macro issues today are largely the same as six months ago. . . To be honest, it's a bit of a mystery why stocks went off the rails yesterday. . . But the fundamentals for stocks aren't much different than they were yesterday.”

This made me remember something I read many years ago, which was written by Professor Hernan Cortes Douglas, former Luksic Scholar at Harvard University, former Deputy Research Administrator at the World Bank, and former Senior Economist at the IMF. He noted the following regarding those engaged in fundamental analysis for predictive purposes:

“The historical data say that they cannot succeed; financial markets never collapse when things look bad. In fact, quite the contrary is true. Before contractions begin, macroeconomic flows always look fine. That is why the vast majority of economists always proclaim the economy to be in excellent health just before it swoons. Despite these failures, indeed despite repeating almost precisely those failures, economists have continued to pore over the same macroeconomic fundamentals for clues to the future. If the conventional macroeconomic approach is useless even in retrospect, if it cannot explain or understand an outcome when we know what it is, has it a prayer of doing so when the goal is assessing the future?”

To better understand this perspective, let’s review some facts from market history. In February of 2009, the Kiel Institute noted that “the global financial crisis has made clear a systemic failure of the economics profession. In our hour of greatest need, societies around the world are left to grope in the dark without a theory . . . The cornerstones of many models in finance and macroeconomics are rather maintained despite all the contradictory evidence discovered in the empirical research.”

In the New York Times in August of 2013, we read that “[t]he trouble with economics is that it lacks the most important of science’s characteristics – a record of improvement in predictive range and accuracy. In fact, when it comes to economic theory’s track record, there isn’t much predictive success to speak of at all.”

And, I have many more examples, but for relative brevity, I am leaving the rest out of this missive.

So, this all begs the question as to why the typical fundamental perspective fails at crucial times in market history? To answer this question, I am going to turn to the work outlined in a groundbreaking book, which I suggest to each and every investor that wants to learn the true nature of financial markets based upon empirical evidence: The Socionomic Theory of Finance, written by Robert Prechter. In fact, many of the quotes above and below have been taken from Mr. Prechter’s seminal publication.

In chapter 15 of the book, Mr. Prechter explains the reason as to why such analysis has been an absolute failure. Whereas the law of “supply and demand operates among rational valuers to produce equilibrium in the marketplace for utilitarian goods and services . . . [i]n finance, uncertainty about valuations by other homogenous agents induces unconscious, non-rational herding, which follows endogenously regulated fluctuations in social mood, which in turn determine financial fluctuations. This dynamic produces non-mean reverting dynamism in financial markets, not equilibrium.”

Moreover, since the efficient market hypothesis (the basis for fundamental analysis in financial markets) is an outgrowth from the world of economics, it has become quite commonly viewed as an unworkable paradigm for financial markets (as noted above) for various reasons. Understanding that an underlying assumption within economics is ceteris paribus, and an underlying assumption in the efficient market hypothesis is that all investors act rationally and with the same knowledge, you can easily understand why it is simply unworkable in financial markets.

Mr. Prechter went on in his book to note:

“None other than the chairman of the Federal Reserve weighed in on this very topic in testimony before Congress. The morning after a one-day 3.3% swoon in the DJIA in 2007, “The nations top banker said he could not identify ‘a single trigger’ that caused Tuesdays dramatic drop.” This is a remarkable admission for a macroeconomic mechanist who advocates “financial engineering.” More recently, August 20, 2015 sported the biggest down day in 18 months for stock prices, yet reporters admitted there was a “lack of major U.S. economic news” to explain it.”

To this date, we still debate the cause of the Great Depression, or the October 1987 market crash, the 2010 Flash Crash, the Asian financial crisis, and many other “anomalies” in the market. In 1997, a Nobel-prize-winning economist noted “The truth is that nobody really imagined that something like the Asian financial crisis was possible, and even after the fact there is no consensus about why and how it happened.”

As Mr. Prechtor appropriately also noted:

“Can you imagine physicists endlessly debating the cause of avalanches? . . . Economists are mystified over the causes of market declines and economic contractions because they are using a mechanical model in the realm of finance where it doesn’t apply.”

In fact, Benoit Mandelbrot outright stated that one cannot reasonably apply an economic mechanical model to the financial markets:

“From the availability of the multifractal alternative, it follows that, today, economics and finance must be sharply distinguished . . .”

From an empirical standpoint, consider that, within economic theory, rising prices are supposed to result in dropping demand, whereas rising prices in a financial market actually lead to rising demand. Yet, most continue to incorrectly apply the same analysis paradigm to both environments.

Where does that now leave us? What is the appropriate and accurate manner in which to view our financial markets?

As more and more studies are being conducted into the psychological aspects of financial markets, we are gaining a clearer understanding as to the true driver of our markets.

Let’s begin with a study entitled “Large Financial Crashes,” published in 1997 in Physica A., a publication of the European Physical Society. Within the authors conclusions, they present a nice summation for the overall cause of the herding phenomena within financial markets:

“Stock markets are fascinating structures with analogies to what is arguably the most complex dynamical system found in natural sciences, i.e., the human mind. Instead of the usual interpretation of the Efficient Market Hypothesis in which traders extract and incorporate consciously (by their action) all information contained in market prices, we propose that the market as a whole can exhibit an “emergent” behavior not shared by any of its constituents. In other words, we have in mind the process of the emergence of intelligent behavior at a macroscopic scale that individuals at the microscopic scales have no idea of. This process has been discussed in biology for instance in the animal populations such as ant colonies or in connection with the emergence of consciousness.”

Therefore, it would seem that the movements in financial markets are driven endogenously rather than the common understanding of it being driven exogenously. Now, let’s further consider a study conducted by Caldarelli, Marsili and Zhang, which was publish in the Europhysics Letters. Within this study, subjects simulated trading currencies. However, there were no exogenous factors that were involved in potentially affecting the trading pattern. Their specific goal was to observe financial market psychology “in the absence of external factors.”

One of the noted findings was that the trading behavior of the participants were “very similar to that observed in the real economy.” Clearly, this further supports the perspective that markets are driven endogenously and not exogenously.

So, as I have noted, the more and more we begin to study the psychological aspects of our financial markets, the more we understand why we see movements such as this past week, even though, as one author put it above, “[t]here is absolutely nothing new in either of these issues, but for some reason . . . the market acts like it is seeing something new.”

But, do you think the great majority of analysts, authors or investors will reconsider their perspectives about market mechanics? It is quite unlikely. It would seem that the desire to apply mechanical causality is permanently embedded within the minds of most investors and analysts alike. As Mr. Prechter also astutely noted:

“Observers’ job, as they see it, is simply to identify which external events caused whatever price changes occur. When news seems to coincide sensibly with market movement, they presume a causal relationship. When news doesn’t fit, they attempt to devise a cause-and-effect structure to make it fit. When they cannot even devise a plausible way to twist the news into justifying market action, they chalk up the market moves to “psychology,” which means that, despite a plethora of news and numerous inventive ways to interpret it, their imaginations aren’t prodigious enough to concoct a credible causal story.

Most of the time it is easy for observers to believe in news causality. Financial markets fluctuate constantly, and news comes out constantly, and sometimes the two elements coincide well enough to reinforce commentators’ mental bias towards mechanical cause and effect. When news and the market fail to coincide, they shrug and disregard the inconsistency. Those operating under the mechanics paradigm in finance never seem to see or care that these glaring anomalies exist.”